Today as much as ever, debates rage furiously in the shared living spaces of students all over the world. The subject? The exhausted histrionics of an eternally contentious but ultimately ineffectual conversation on capitalism and communism. You may have visited, or even lived in one of these homes, and been caught in the crossfire between an Ayn Rand acolyte and a staunch Marxist. These arguments are tedious, but what is interesting is the ways in which the aggressive competition between these two very disparate ideologies have informed and constructed cultures and belief systems that are clearly still relevant today.

Without consuming precious word space on the long and tragic histories of Russian or Chinese communism, we can begin at least with the philosophy which lead these two great nations into economic, social and cultural instability. For his part, Marx devised that “class conflict within capitalism arises due to intensifying contradictions between highly-productive mechanized and socialized production performed by the proletariat, and private ownership and private appropriation of the surplus product (a.k.a profit) by a small minority of private owners called the bourgeoisie. As the contradiction becomes apparent to the proletariat, social unrest between the two antagonistic classes intensifies, culminating in a social revolution.”

Not limited to economic, industrial and legal policy, the revolution that ensued permeated every facet of citizen life. Even would-be avant-garde designers committed their talents to the motherland, producing some of the most unforgivable utility wear ever imagined. Certainly the most interesting phenomenon (for a non-communist observer) was the revolution of artistic style.

Less a reformation than a total erasure of everything that had gone before it, the people of Russia (and later China) had invested all their creative efforts in an ideology that took political form. In such a state of radical progress, Russia (and China) could no longer truly be represented by the highly skilled, aristocratic styles of the bourgeoisie, but with the great failure of western avant-garde art to capture the heart and mind of the proletariat, Communism needed to develop its own distinct forms of cultural expression.

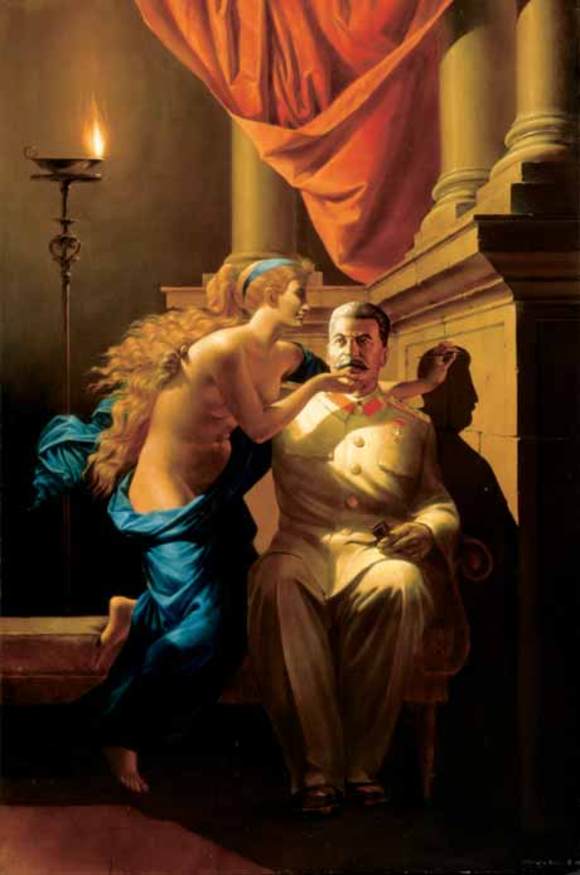

By the 1930s, Malevich was trying his hand socialist realism, as were many painters, depicting the simultaneous efficiency and humanity of the soviet system, (around the same time that bloody ‘collectivization’ was taking place on farmland across Russia). In sculpture, Iofan was unambiguously heroicising political figures and generally lauding socialist romanticism in the form of terrifyingly large bronze sculptures that would represent Russia at the Paris World Fair in 1937.

Just over a decade later, Mao Tse-Tung became chairman and Chinese artists were quick to begin replicating Russian exports of socialist realism and socialist romanticism with a distinctly Chinese flavor (imagine Mao’s face where Stalin’s would’ve been).

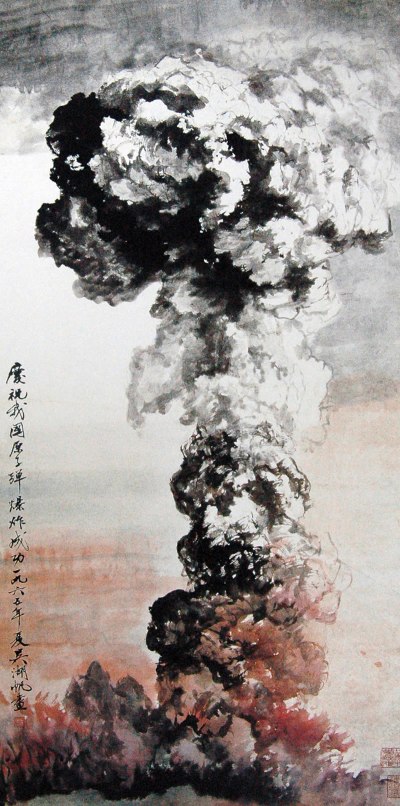

Interestingly, the Chinese had their own highly skilled style of “literati” art, in the form of Chinese brush painting, known as guó huà. Although the Cultural Revolution had, in many ways, meant a total breakdown of the infrastructure of Chinese cultural tradition, it was not obliterated by merely painting it white and then painting it black. There were somewhat unsuccessful attempts to update the guó huà with western graphic styles, but it was not until 1947, when Mao released the Manifesto of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army, that the guó huà was finally beginning transform into the people’s art.

The propaganda of the time authorized the rustication of thousands of Chinese youths, and stipulated the necessity for youth to learn the knowledge of the peasants and respect physical labour. In the following years, the presence of educated youth in rural communities led to an exchange between the styles of the art schools and traditional peasant art. This was primarily evident in Yunnan province where collaborating rusticated youth and peasants became known as the Hsien painters, celebrated for the unification of Socialist realism, romanticism and guó huà. This visual unity was boasted on postage stamps and domestic imagery, and gained international following from appropriation by artists like Wu Hufan.

Communist art continued to be produced in great quantities for almost thirty years after the rustication, and in this time, western tastes for girl-meets-tractor painting had steadily waned.

It had almost completely fallen off the Western radar until 1974 when the post-facto titled Bulldozer Exhibition took place in Moscow. Infamously named after its forcible destruction by water canons and bulldozers, the exhibition contained the work of several artists expressing seditious content. The since-exiled organizer, Oscar Rabin declared that the show was intended as an explicit protest against an oppressive regime.

The occidental art centre realized that this event highlighted what capitalist Westerners already knew but wanted to hear, that communism had failed. It also drew attention to the fact that there were subversive factions in the East – factions who were creating art like nothing being produced in the West at that time. Western audiences could now indulge in forms of modernism and pop art that had filtered through the iron curtain with a lingering, but not totally convincing, ‘you told us so’.

SOTS artists like Kabakov and Komar & Melamid soon discovered that the West was thirsting for a cocktail of socialism-in-strife meets political over-identification, and promptly generated an immensely profitable market between artists from communist states and buyers in the West. With Gorbichev in the Kremlin, these artists could more openly criticize the native government that had censored them. Moreover, they were able to mock the foreigners that had threatened to subjugate them, by enjoying astronomical fame in the art world and more importantly, by cashing the massive cheques that the West was paying for a taste of Eastern disenchantment.

With the fiscal directives of Deng Xiaoping in from 1978 onwards, China moved to build a middle class, reinforcing a domestic market that could protect their economy against interactions with weaker economies. In 1993, after 15 years of progress towards a market economy, 14 Chinese artists were shown at the Venice Biennale that was memorably known as the ‘Chinese Biennale’. The presence of contemporary Chinese art had created a stir, exciting Western audiences once again, this time from art beyond the Great Firewall of China. In particular, Wang Guangyi’s poppy imagery offered a home plus for Western audiences in its reference to modernism, but also demonstrated an exact knowledge of the trajectory of SOTS art, launched a decade earlier.

An entire art-making precinct was constructed, known as Precinct 798, where international art buyers could travel to Beijing to purchase work directly from artist studios. The success and economy generated by the Venice Biennale and Precinct 798 led to government recognition of China’s art market, occasioning the first Shanghai Biennale in 1996.

While many consider the opening up of trade and culture in China to be a hopeful progression, political artists like Ai Weiwei revile the notion of government intervention in the arts, perhaps rightly, fearing its use as a vessel for political propaganda. It brings to mind the tragic paradox of the artist, who must choose to be avant-garde, starved and brilliant, protesting against a government that has abandoned the arts, or stifled, unable to procure an original idea, growing fat off the teat of government funding. Although I would say that Ai Weiwei is neither starved nor stifled.

It seems that after a century of communism, we in the West can finally rest assured that the threat of socialism is no more. We have the art to prove it.