Since 2009, Dolce and Gabbana's advertising campaigns have embellished ritual, culture and tradition to create cinematic images of Sicilian life. While these photographs borrow from neorealism, the inevitable glamour of the photographs insinuate an invented reality. The dialogue between characters draws on the social experiences specific to Sicilian people, focussing on relationships between men, women, women in the male domain and particularly family dynamics.

I have selected a series of photographs by Mariano Vivanco from Dolce and Gabbana's 2012 collections (both summer and winter) as examples of the fashion house's ability to pinpoint the cultural essence of a race, deconstruct it, locate those elements permissible as haut-couture and reinvent them to produce an image that is as visually engaging as it is marketable.

The work I am making in relation to this piece is exploring if, through playfulness and criticality, misrepresentation can subvert stereotypes. In order to uncover the factors that comprise these stereotypes, it is necessary to look at the thematic content of the images.

How do these images compare with or deviate from neorealist styles, and how does self-reflexivity position these images between high and low art?

Within the series, some photographs depict scenes of festivity, celebration and 'La Dolce Vita', or the good life, yet others demonstrate more simplistic scenes such as the humble family portrait. The shifting context of the images from neorealist characterisations of poverty (mitigated here as modesty) to an entry into bourgeois territory can appear arbitrary, but it is possible that Dolce and Gabbana use this dichotomy of old and new to evoke a sense of timelessness, explicitly in their collections and implicitly within Sicilian culture.

The presentation of cameras within photography also raises the question of the significance of self-reflexivity within the images. The production designer's apparent disregard for continuity emphasises that the images are a series of advertisements and as such may be forgiven for such discordance, but there is more to the composition than that. That there exists any camera at all within the images suggests that Vivanco has given consideration to both art historical precedence as well as the pervasive influence of new media communication technology and its infiltration in daily life and thus, the arts.

This image features the hallmarks of contemporary art/life: a camera phone, a full colour photograph and an unorthodox composition using cropping.

Alternatively, this image uses the same devices in exact opposite: a sepia tone, a vintage camera (used by a man, not a woman) and the formal structure of a family portrait.

As for relationships between men, how are masculinity stereotypes reinforced or challenged?

Several images within the campaign depict a suggestion of daily life for Sicilian men. They are portrayed in large groups, casually chatting and joking with one another, apparently doing little else. When these men aren't avidly conversing, they are brazenly pursuing (in pack formation) a pretty girl in white crochet or a vixen in black lace. The suggestion of their relaxed nature and sense of playful brotherhood is also met by the darker side of the Sicilian male psyche: that of pride, ego and revenge. One such image very subtly alludes to the preamble of a conflict: while two men face each other off, a group of men in the background are discussing something with grave expressions, as a woman (or a prize) stands alone between them.

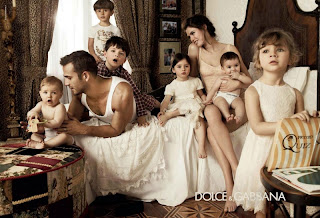

The final facet of the Sicilian man according to Dolce and Gabbana is that of the stupendously potent, loving and protective father. While most of the images of large family scenes contain a patriarchal type, there is one image in particular that conveys this aspect so boldly that it borders the absurd. Somewhere in Sicily exists an opulent room (n.b. the leopard print curtains), where a man and woman who both appear younger than thirty have somehow produced six children.

The image cleverly associates luxury with masculine fertility, taking virility to the ultimate hyperbole - an artful strategy for countering the 'masculine' tendency to dress simply and cheaply.

Do Sicilian women live in the male domain? What are the roles of women in Sicilian society?

A common theme runs throughout the campaign: the image of a solitary woman who seems to enjoy being surrounded by men. She is the object of desire, a symbol of pursuit or achievement, or a reflection of a man's status in the world. According to this campaign, women come in three forms: the first is the elderly matriarch whose sexual appeal has long since faded and so busies herself with domestic chores, craft-making and caring for her ever expanding family. The second is the naive young thing who is not quite a 'woman', but still sexually desirable. Finally there is the embodiment of passion, the perfect union of domesticity and sexuality (played convincing by Monica Bellucci in 2012 and somewhat artificially by Madonna in 2010) - this woman, of course, is the 'Sicilianized' femme-fatale. While the three women are clearly living in a man's world, some power is evident. Aside from their skills in areas generally uninhabited by men, the woman's command of persuasion through sexual power is clearly exaggerated. Though she may be politically, culturally and financially tethered to her male counterpart, her ability to please a man allows him to become the vehicle through which she can lead a more independent life.

The Sicilian man is so irresistible that this woman doesn't mind the leering and joking of his companions. Contrary to a dominant and enduring dogma of sexual politics, this woman is not ashamed of her sexuality. In fact, in this man's arms she is wilfully communicating her sexual desire.

An analysis of family dynamics presents the final question: How authentic is a woman's power and to what extent is she an authority? How is homosexuality expressed within this dynamic?

Although clearly contrived, this image depicts the tribulations of child-rearing in a lighthearted way. A young boy is being reprimanded for upsetting (assumably) his younger sister. While Bellucci scolds the boy (with the signature 'wog' gestures of brandishing hand movements and a face whose frozen expression is one of fury), the other two 'types' of women are amused by the histrionics of the situation. The younger woman, perhaps because such strenuous activity will not concern her for some time. But the matriarch's gaze is not directed at the instigator of the drama a.k.a the boy, but at Bellucci. Perhaps she is laughing for the fond memories of her similar experiences, but her mirth could just as easily stem from a superciliousness that subtly undermines Bellucci's authority. This interpretation implies that it is only through old age (once the follies of sexuality have diminished), that a woman can gain respect within her community.

Interestingly, a subdued homoerotic element exists within many of the campaign's photographs. While female homosexuality is totally omitted (there are barely more than one woman in many of the images), certain dynamics between men clearly retain some essence of the homoerotic that frequents male fashion photography. While physical affection between men is common in Italy (as in many non-Anglo parts of the world), the seriousness of these boys' faces, their shirtlessness and the body language enunciated by one turning enticingly away from the other, entertains the potential for gay family members not only existing, but being accepted within the Sicilian family unit. This image overwhelmingly reminds us of the power of advertising to understand the desires of the consumer and create a world where those desires might be realised, if only as a model for actuality.

No comments:

Post a Comment